| |

| Downtown Vancouver |

| 1 p.m. – 11 p.m. |

| June 15, 2011 |

| |

| photographs of a Stanley Cup riot |

| |

| Face Paint & Tear Gas |

| Beers & Big Guns |

| Sunshine & Smoke |

| Group Cheers & Cell Phone Pics |

| Anguish

& Altercations |

| Disappointment & Police Cordons |

| Idle Crowds & Broken Glass |

| |

| by Jeff Hohner, all photographs © 2012 |

| It was bad timing on my part. I had moved from Vancouver to Castlegar, B.C. in May, 2011 during the late stages of the Vancouver Canucks' most successful playoff run in years. Vancouver is even more magical than usual during the hockey playoffs when the Canucks are in contention. Perhaps this happens in all big cities with a winning hockey team, but I've only experienced it in Vancouver: the weather is warm, everyone's windows are open, and the city becomes one enormous shared living room. When the team scores, a collective cheer fills the air and echoes through the neighbourhood. Before and after games, the streets come alive with people in jerseys and face paint. As a street photographer, I had photographed fans all spring; but now that events were reaching their climax, I was elsewhere. |

| |

|

| Face paint: Robson Street, early afternoon.

|

| |

| The Canucks had persevered through several tough playoff rounds to make this year's Stanley Cup Finals. Many fans of professional sport consider the Stanley Cup the most difficult of all sports championships to clinch. This is because of the number of games a team must win in short order and in the face of the injuries that inevitably accompany the intensified competition of the playoffs. Vancouver’s experience this year was case in point. Fans had endured many close games, over-time wins and losses, and a nail biting seven game series against the team's nemesis, the Chicago Blackhawks. The Blackhawks had eliminated Vancouver from contention in the previous two years of playoffs... but not this year!

|

| |

|

The Finals were just as nerve-racking. Vancouver had finished the regular season at the top of the league due to their elegant, highly skilled play. This play had seen us through to become Western Conference champions, but having come this far, our team was being stopped in its tracks by the rough, injurious tactics of the Boston Bruins, our adversaries for the Cup. Vancouver fans were frustrated but hopeful. Desperately hopeful, because, despite building several strong teams over their 40 year history, the Canucks had never won the Cup.

|

| |

|

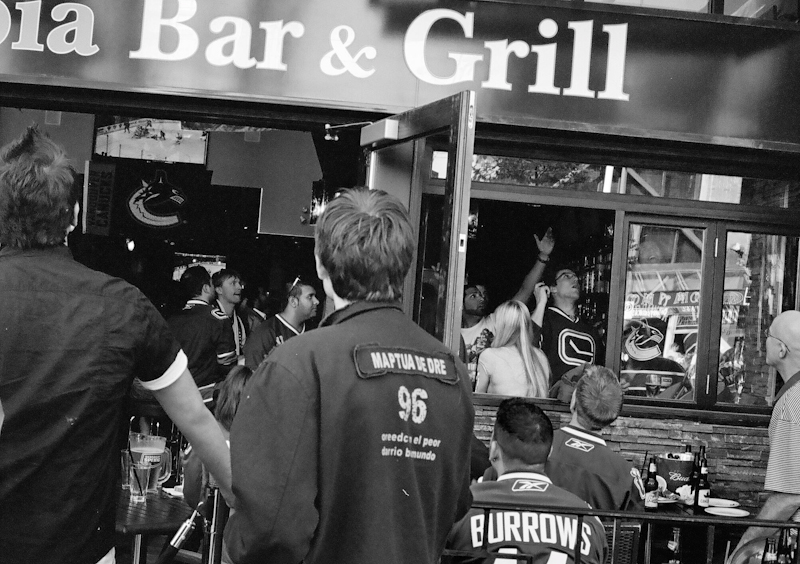

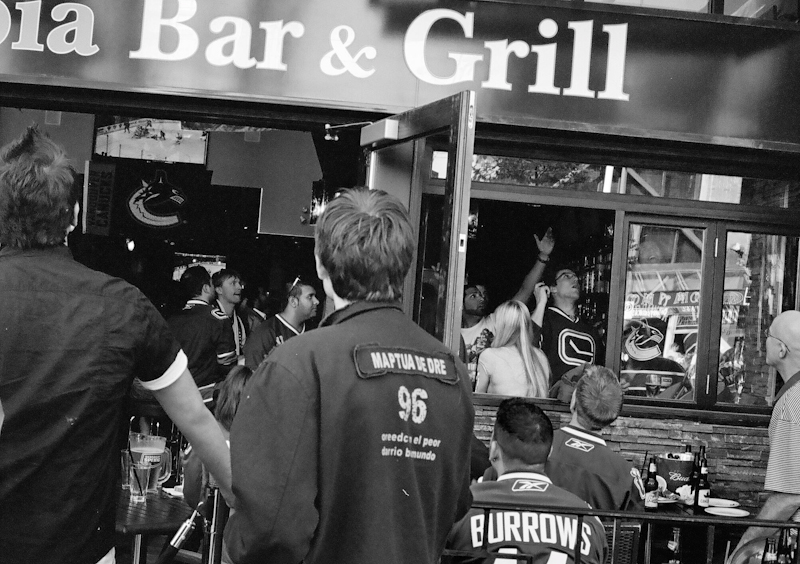

| Beers: fans inside and outside a Granville Street bar cheer during the early first period.

|

| |

| Like all playoff series, the Finals were best of seven — we needed to win four games. Vancouver narrowly won the first and second games but, tired and intimidated by Boston’s physical play, we folded in the next two. And those loses were both demoralizing drubbings. The city had gone into the series excited, confident, high. But now we paused and vowed to play tougher.

|

| |

| It worked. We won the next game, putting us within one win of the Cup, our first Cup, the long overdue Vancouver Stanley Cup. But again, we had won by only one point. Vancouver fans were noticeably less cocky despite the series lead.

|

| |

| Then, we lost to Boston in game six. It had been 39 years since the Bruins last possessed the Cup and they wanted it as badly as we did. It had all come down to one final game. Win or lose, something big was about to happen on Vancouver streets.

|

| |

|

| Sunshine: police and the public enjoy the afternoon on Granville Street. People dance to drums at right.

|

| |

| I was sure people would riot. I wasn't even in Vancouver and I could feel it in the air. In 1994, the Canucks had also gone to game seven of the Finals, they'd lost, and a riot had ensued. I was only a fledging Canuck fan then and wasn't making many photographs at that time but I had been tempted to go downtown and see what all the fuss was about. I didn't and the anthropologist inside me always regretted not going. So this time around, on the morning of the game, I hopped on a plane and flew to Vancouver with several cameras.

|

| |

|

| Group cheers: arms and flags are raised on Georgia Street during the second period.

|

| |

| I took an Olympus OM-2 with Zuiko 24mm f/2.8 and 85mm f/2 lenses. I also took a Pen FT. I love half-frame cameras because I'm cheap. They really stretch my film dollar. The FT also let me share lenses. The lens that wasn't mounted on the OM-2 was on the FT and vice versa. This gave me the additional fields-of-view of 35mm and 120mm lenses given the magnification factor of the FT-to-OM lens adapter. Last of all, I hung a Pen D3 around my neck. It is tiny and has a fast f/1.7 45mm-e lens that I knew I'd need after dark. I kept all three cameras loaded at all times which gave me the choice of wide, normal, and tele focal lengths. Who needs a zoom? (Help! My camera straps are tangled again!) |

| |

| All in all this rig worked well. With everything around my neck I didn't even need a camera bag. While shooting the 2010 Winter Olympics celebrations I learned it's easier to navigate tight throngs with all your gear in front of you. A camera bag on your hip or back is at risk of being squished or even opened without you knowing it. I took a small bag anyway, in case I got arrested and needed to give up my gear temporarily. I was ready for anything!

|

| |

| Once in town, I stocked up on film. I shot Kodak's C-41 B&W, BW400CN, so I could have it processed by my favourite Vancouver lab tech, the lovely Lisa G. at London Drugs Robson Street. I started with a dozen rolls but bought more as the day went on. In the end, I exposed 18 rolls of film, more than half of it as half-frame.

|

| |

|

| Anguish: hard feelings begin to show in the middle of the third period as Vancouver continues to trail badly.

|

| |

| I was on the street by 1:00 p.m. and started shooting along Robson Street, my old stomping ground. Just as I had done during the Olympics, I worked the crowds along Robson toward the sports bars on Granville Street. I’d also covered this ground on the evening of the game seven win over Chicago two months earlier. Like one of the competing athletes themselves, I felt well practiced for whatever lay ahead.

|

| |

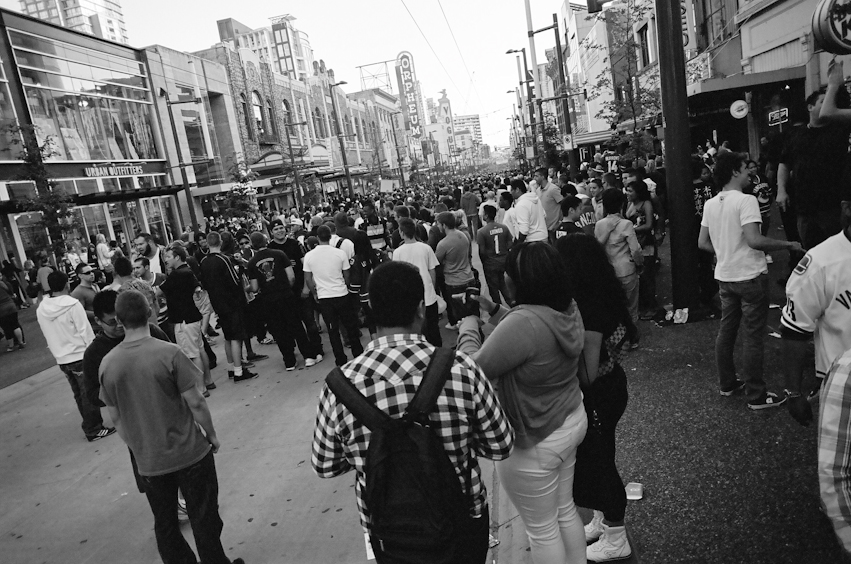

| Once the game started, I moved down Granville to Georgia Street and across to the huge 'fan zone', the stretch of Georgia closed to traffic between Richards and Hamilton Streets. Here, 100,000 people filled the six-lane street. They stood shoulder to shoulder watching a big screen broadcasting the game at Hamilton and Georgia.

|

| |

| The game did not go well. Despite a strong start by Vancouver, Boston scored first. Vancouver could not reply and went to first intermission trailing. Halfway through the second period, Boston scored again. This was unfortunate but not fatal. A two goal deficit is difficult but entirely possible to overcome in hockey. Goals can come quickly and from nowhere, especially during heightened play. Fans remained upbeat. Vancouver was getting plenty of chances to score; we were out shooting Boston, but Boston's goalie, Tim Thomas, continued to be, as he had been almost all series, invincible.

|

| |

| At the end of the second period, Boston scored again, and things started looking bleak. The third period was scoreless. As it ticked on, hope faded. The crowd became silent and still. People's eyes wandered off the screen to stare at the ground or sky. And on top of all this misery, Boston scored one last goal, albeit on an empty net.

|

| |

In the end, the Shots Against and Saves statistics said it all.

Thomas: 37 shots / 37 saves. Luongo: 20 shots / 17 saves.

|

| |

|

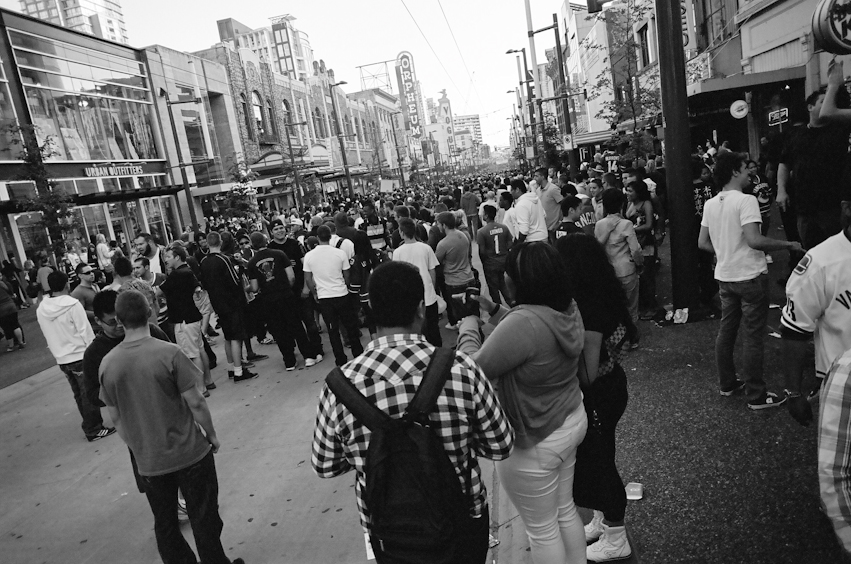

| Disappointment: fans mill on Granville Street following Vancouver's loss.

|

| |

| Towards the end of the third period I began to run out of film. I retraced my steps to buy more at Granville and Georgia, then decided to return to Granville Street to photograph the disappointed hoards knowing they'd gravitate there after the game. This was a fateful decision because the riot started on Georgia Street in front of the Post Office and not on Granville. I missed photographing those events but I didn't have to wait long for other mayhem.

|

| |

|

| Idle crowds: there is little to do on Granville St after the game.

|

| |

| About half an hour after fans flooded back to Granville, a commotion in the direction of Nelson Street drew me that way...

|

| |

|

| Cell phone pics: fans pose for friends on Nelson St between Granville and Howe.

|

| |

| Again, I missed the flipping of cars and smashing of car windows. When I arrived, a tight crowd had formed around a flipped car in the middle of Nelson Street between Granville and Howe. Young men took turns climbing on the undercarriage of the car while the crowd enthusiastically took pictures of them with their cell phone cameras. When the crowd, having grown bored with this, eased, a young man exhorted people to attack the car again. He appeared to me to be a politically motivated agitator of the type that had acted up at the Olympics the previous year. I saw a few of these folk on the streets during the evening but not as many as during the Olympics. I don't think they were responsible for provoking the crowd to riot in any major way. Alcohol, youthful folly, and —most importantly— lack of a post game event to help fans decompress were, in my opinion, to blame.

|

| |

|

| Big guns: riot police survey the crowd after having cleared the road about an hour and a half after the game. Nelson St between Granville and Howe.

|

| |

| The police were very measured in their response to the crowd. They took some time to appear at Nelson and Howe. Clearly they had had to restructure themselves from their friendly pre-game and game-time squads. Those squads had mingled with the crowds, smiling and talking with people. This tactic of engagement had worked well during the Olympic gold-medal hockey game, an event with similarly sized and charged crowds. Sadly, it didn't do the trick today. True, the home team (Team Canada) had won the Olympic contest, but I'm not sure this was significant: Canadian hockey fans have rioted after the winning of the Stanley Cup as well as after the losing of it. I believe that the different natures of the Olympics and the NHL Finals were more determinative (the Olympics having had an older, more mixed fan base, a more relaxed and festive atmosphere, and numerous post-event activities), and that the police were made overconfident by the success they had at the Olympics.

|

| |

|

| Tear gas: gas wafts over the crowd on Nelson Street below Howe.

|

| |

| The police also had their hands full elsewhere downtown. A much larger and crankier crowd (I would later learn) had already vandalized cars and set them on fire in the fan zone on Georgia Street. From what I saw, the police did a good job of deploying their resources on several fronts at the same time. The officers attempting to clear the streets showed restraint and even some humanness. I didn't see any batons used or people roughly handled in the three zones I watched them clear between 8:00 and 11:00 p.m. Mind you, the crowds in these areas were peaceful. Sure, some mooned the cops and a few threw bottles at them (plastic water bottles), but 75% of people on the street were simply curious gawkers. Of the remaining 25% (the drunk and disappointed young men), most were itching for nothing worse than breaking a hockey stick on the ground in frustration.

|

| |

|

| Smoke: view from Granville St of smoke from cars burning a few blocks away.

|

| |

| As the night wore on, things got a little uglier. As sensible folk went home the proportion of jerks rose. Public drunkenness isn't pretty, and I witnessed several instances of testosterone fuelled belligerence and a few fights.

|

| |

| I followed smoke to cars burning outside the Hudson's Bay on Seymour Street at Georgia. Some windows at The Bay had been broken. A small number of people worked at breaking more, each in a desultory way. Every now and again, someone would find something to throw or bash with, meet with little success, then wander on. Almost as often, someone else would challenge them to behave and they would move along without vandalizing the store. All of the altercations of this kind that I saw resolved themselves peacefully. No one wanted conflict, some just wanted mischief.

|

| |

| And some wanted stuff. People looted. Again, the action at The Bay was low-key. Perhaps the looting elsewhere was different, but I saw only tentative, sporadic, limited looting. People entered the store cautiously by ones and twos. They emerged with small (probably expensive) items like purses.

|

| |

|

| Altercations: young man with bloody knees relaxes with friend on Robson Street between Granville and Howe, around 11 p.m.

|

| |

| My goals for the day were several: to enjoy my hobby—large, festive, feisty crowds are candy for street photographers; to experience the moment and be a part of history (for better or worse)—I am a Canucks fan (for better or worse); to document events in a quasi-journalistic sort of way—I had no press credentials and no real intentions of shopping my work to news organizations but wanted to create a record of the day nonetheless; and to —with luck— make some good pictures.

|

| |

| The shoot was the culmination of my Vancouver street photography career. I had a gas roaming my old neighbourhood with cameras one last time. I also got to experience a riot. I was lucky it was a relatively tame one. Sure there were tense moments, but overall the mood on the street was relaxed, even at the height of the chaos. I attribute this to the mixed crowd and the well-behaved police. Perhaps I give the police too much credit for having avoided the abuses that typically accompany riot policing, e.g. gratuitous bludgeonings and indiscriminate arrests. The police were terribly outnumbered and perhaps this made them watch their P's and Q's. I saw only one arrest. Police cordons kettled crowds slowly from one block to the next, but they only had enough officers to push, not to corral. Limited contact between the police and the crowd may have helped keep things cool.

|

| |

| As for documenting the event? I have a new appreciation for photojournalists. To photograph historic events you must be in the right place at the right time. This is even more difficult than it sounds. I knew something very big was going to happen and had narrowed it down to happening within a few small blocks, but I still missed it (the ignition point of the riot). I now know that a photojournalist needs more than knowledge of their subject and good photographic instincts. They also need reconnaissance. If I'd had a smartphone, I may have been better able to find key spots to photograph. Regardless, I'm very happy with the photos I made. Street photography is easy that way: great photos are always at hand if only you face the right way and click at the right moment.

|

| |

| Speaking of smartphones, video clearly trumps still photography for documenting a riot. Most YouTube videos of the riot capture the chaos far better than photos. Photographs need context to become documents, captions to ground or untangle the unavoidable ambiguity of a frozen image. The action in video quickly provides its own context. Of course, the ambiguity of the photograph is what allows it to be art. Next time I shoot an event I'll stick to making art. The kids with phones have the documentation covered, and writing captions is a lot of work!

|

| |

|

| Police cordons: police slow their advance along Seymour St around 10:16 p.m.

|

| |

| In all, this site contains 172 photos displayed in 14 categories. The categories are thematic and largely chronological. You can follow the events of the day, as I witnessed them, by scanning the page from top to bottom.

|

| |

| Click on a photo to see the next photo in that category. Within each category, photos are not strictly chronological. They are arranged to best serve the photo essay. The strongest photos appear at the beginning of each category. My favourites appear first.

|

| |

| The dots below the photos indicate which photo in the category you're viewing; they also link to the photos themselves so that you can jump between photos.

|

| |

| The triangle at the end of the row of dots links to a menu at the top of the page. The categories are listed there as pairs that juxtapose events before and after the start of the riot. The lefthand elements of the pairs follow each other chronologically, but the dictates of poetry required the righthand ones not.

|

| |

| As you explore each category, the selections you made in other categories are preserved. If you come up with a selection of pictures you like better than my default 'firsts', make a bookmark of the page; the URL of the page encodes your selection. Email it to me to share your fave 14.

|

| jeff dot hohner at gmail dot com

|

| |

Notice: Undefined index: jshohner-riot-photos in /hermes/walnacweb03/walnacweb03ag/b839/pow.defenestrate/photos/htdocs/riot/index.php on line 825

Notice: Undefined variable: verified in /hermes/walnacweb03/walnacweb03ag/b839/pow.defenestrate/photos/htdocs/riot/index.php on line 825

|                | Broken glass: man throws something in front of The Bay on Georgia Street.

| | |

| This last section includes shots of looting. I feel strongly that my photos not be used by the police to identify and charge people with crimes. Part of this attitude is political. Yes, theft is wrong, but I think there are better ways to ensure public order than pillorying young people who've made poor decisions, very likely out of character, that harm no one (spare me mention of higher insurance costs, like I said, there are ways to avoid riots and keep insurance costs down if we really want to make such investments in society). Furthermore, the backlash against the rioters facilitated by social media shows how readily we moralize and scapegoat people instead of seeking the causes of events. I want no part of that.

|

| |

|

Most of this attitude, however, is practical. If photographers come to be perceived as an extension of the police, our ability to make photographs will be more difficult.

|

| |

| As it was, I witnessed one woman having her camera taken from her and smashed during the looting (see photos in the Altercations section). I was very close to her but didn't intervene because I'd decided to play photojournalist. Under normal circumstances on the street I interact as little as possible with subjects for artistc reasons, so it was easy for me to extend this detachment to serve hard reportage. Regardless of these 'professional' standards, I was prepared to intervene to prevent serious physical harm to another. Throughout the evening I hovered a lot on the fringes of altercations. If a situation seemed dicey, I'd hover longer until it diffused. This strategy wasn't entirely altruistic, however. It served photographing the fullness of events too.

|

| |

| Luckily I didn't witness any serious fights —at least none involving people who couldn't take care of themselves— so didn't have to engage people as a citizen rather than as a photographer. The smashed camera incident didn't escalate; smashing the camera must have fixed whatever perceived problem existed for the attacker. Somehow I escaped offending them too, even with three cameras around my neck! The closest I got to testing my boundary was running after a group of guys chasing a 'Boston fan' until I was sure their target had outrun them.

|

| |

|

| If you'd like to see those pictures that are greyed-out above, enter the name of Jeff's former boss:(Cookies must be enabled in your browser.) |

|